Substrate Innovations for Growing Green Roof Plants

Advertisement

Michael Davenport with Omni Ecosystems holds a clod of growing media from its headquarters green roof. Plants sprout up and out of the lightweight, nutrient-packed multi-layered substrate developed by Omni Ecosystems. Industry innovations are one key source of innovation that challenge the green roof industry to flourish. Photo: Bruce Dvorak

Introduction: Substrates and the Urban Land Pyramid

In her 1962 international best-selling book, Silent Spring, marine biologist Rachel Carson tells a compelling evidence-based story on how all life on earth is bonded to soil, and what can happen to us and the environment when those realities are ignored. Carson says, “The thin layer of soil that forms a patchy covering of the continents controls our own existence and that of every other animal of the land. Without soil, land plants as we know them could not grow, and without plants, no animals could survive (Carson 1962).”

Aldo Leopold explains why, “Land… is not merely soil; it is a fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals (Leopold 1966).” Leopold’s explanation is founded on the science of the Land Pyramid, where the sun's energy is transformed as it flows through plants, soils, animals, and the biosphere.

In cities, buildings and pavements without green infrastructure seal the land and impair the Land Pyramid and the biosphere and contribute to urban heat islands, flash flooding, stream channel erosion and many other negative environmental and human health issues. However, innovations such as green roofs, green walls and rain gardens revive and heal urban ecology through an emerging green economy that is supported through blended engineered media for growing plants.

Advertisement

At the Phipps Center for Sustainable Landscapes in Pittsburg, PA the site and building accomplish net energy, net water through an integrated design process that employs natural soils and blended substrates. The energy cycle is retained through green roofs, green walls, rain gardens, constructed wetlands, and native plantings. Photo Bruce Dvorak

Green roofs facilitate a “win-win” solution for urbanized landscapes. The fountain of energy present in soils typically displaced by building construction is mimicked and restored through green roof technology. Developments with green roofs often reap immediate and decades-long environmental and economic rewards and can typically recover costs within six years after installation. (General Services Administration 2011, Mahdiyar, Tabatabaee et al. 2021). It is through the innovations in the development of the growing media, or substrate (Best, Swadek et al. 2015) that green roofs have become a proven and value-driven technology (Shahmohammad, Hosseinzadeh et al. 2022).

Three Domains Guiding Innovation in Green Roof Substrates

Through the decades, numerous green roof substrate blends have been trialed, installed, and researched and reported on (Kader, Chadalavada et al. 2022). Substrates are not ‘soil’. They are made from inert, organic and living organisms which are combined to support and regenerate the plant’s roots, shoots, leaves, and reproductive cycles. A supportive substrate meets the growing needs of the plants. While there is no universal substrate that performs well for every kind of green roof, there are general characteristics that are salient across successful green roof plantings anywhere. Key attributes of a media for green roofs include appropriate levels of nutrients, moisture retention, air exchange, microflora, structural support, drainage, thermal moderation, and regeneration of organic matter over time for the selected plant community (ASTM E 2400 2006).

(left) Image shows rooflite® extensive growing media that was originally installed on green roof experimental plots at Texas A&M University in 2012 in Tecta America® trays. Shown here in 2022, the media was repurposed in Bioroof® modular trays mounding from 8” at the edges to 12” in the center and was seeded with a native Blackland prairie mix. (right) Sunlight, precipitation, and supplemental watering brought the seed and substrate to life after one growing season (Dvorak and Woodfin 2023). Photo: Bruce Dvorak

When applied to green roofs, the adage “right plant, right place,” means that plants are flourishing on a green roof year after year. It means the design team knew how to design a green roof so that the plants are well-adapted to the substrate and deliver multiple benefits. The amount of sunlight, moisture, temperature, air exchange, nutrients, microbial activity, and substrate depth are all suitable for the desired plants. Substrates are dynamic, meaning their moisture and organic content are in flux. Because substrates are dynamic, a designated person needs to keep watch of a green roof over time to understand how the substrate is performing and make adjustments when necessary.

Because of these technical realities, the design and monitoring of successful and reliable substrates for green roofs have demanded input from three domains of influence. Over many years, needs emerged to guide the design, construction, maintenance and monitoring of green roofs. This article explores three key domains of innovation for green roof substrates: guidelines, industry development, and research and performance.

Advertisement

Substrates supporting the green roof vegetation at the UfaFabrik buildings in Berlin, Germany, were installed in 1984. The waterproofing, substrates, and plants have delivered multiple ecosystem services and economic benefits for more than forty years (Kaiser, Köhler et al. 2019). Much has been learned from longstanding green roofs such as these. Photo Bruce Dvorak 2013

Green Roof Guidelines

In efforts to provide a reliable source of knowledge and support to the emerging green roof industry in Germany, the FLL Guidelines for the Planning, Construction and Maintenance of Green Roofing were first developed in the early 1980s, are periodically updated, and were first published in English in 2002 (FLL 2002). They are written by experts from three sources of input: the design professions, construction and maintenance industries, and academics researching green roofs. They came together to develop a set of guidelines for green roofs that could be used by those with different levels of knowledge and experience. Today, there are several organizations from different climates of the world that have evolved green roof guidelines for their region (Catalano, Laudicina et al. 2018).

Green roof guidelines cover all aspects of green roofs from design to installation and performance monitoring (Philippi 2005). Perhaps one of the most universally adopted and modified subsections of guidelines includes guidance for substrates, vegetation, and monitoring. While there are many arguments for or against the use of green roof guidelines, their validity is demonstrated when designers attempt to develop custom blends blindly, with no prior knowledge or reference to what has worked over the past 50-plus years on green roofs. Guidelines are a starting point. In North America, most blenders began working from knowledge of the FLL Guideline media recommendations for substrates. Blenders began with referencing and experimenting with knowledge of the FLL Guidelines for green roofs before promoting their products to local markets.

The ASTM guidelines for vegetated roofs apply much of what was learned about substrates since green roofs were introduced to North America (ASTM E2777 14 2014). However, there is still work to be done, as new markets have emerged in different climate zones in North America that are very different from the climates of Germany and Europe (Dvorak 2011). As green roofs reach out into new markets, more innovation will be necessary.

While prairie vegetation may grow in 5 or 6 inches of substrate east of the Mississippi River, its application in Texas typically requires deeper substrates in locations that frequently experience prolonged drought and greater heat stress. Here a 10-inch-deep substrate (25 cm) supports Blackland prairie vegetation above a kitchen house outside of Austin, Texas. This green roof’s substrate is a proprietary custom blend developed by Blackland Collaborative staff, based on years of research and development. Photo Bruce Dvorak

Green roof guidelines for substrates inform about media particle size, moisture needs, expectations for compaction and stability, depth of substrates for different forms of vegetation, and nutrient performance expectations (Ampim, Sloan et al. 2010). Key elements provided in guidelines for growing plants in green roof substrates include guidance regarding:

Bulk density (weight)

Porosity and moisture management

Nutrient management

Depth of substrate for different forms of plants

Watering requirements for plants in substrates

Establishment of microbes and microflora

Thermal properties of substrates

Substrate stability over time (shrinkage)

Substrate stability during establishment (wind and water erosion)

Slope stability

Testing and monitoring of substrates

Particle size distribution

The challenge is that sometimes, if only one or a few of the substrate characteristics are not right for the selected plants, the vegetation can decline, perish or become outcompeted by voluntary vegetation (weeds). I have visited green roofs where a custom blended media was designed with little or no reference to guidelines. The blend contained a very high percentage of organic matter (40%). Although it performed well initially, the substrate depth shrank from 9 inches deep to 5-4 inches deep in just a few years. As the organics dissolved, the media devolved from well-drained conditions supporting drought-tolerant vegetation to a substrate with poor drainage characteristics and became suited for mesic or wetland plants. Large areas of the vegetation had died back. However, this was one installation, and there may be substrates with higher organic content that are stable. Substrate blenders should provide documentation regarding a record of performance for their blend.

I have also visited more than a few green roofs where the substrate was poorly matched to the desired vegetation. Mismatched substrates included those that were too xeric (dry) for the selected plants, held too much water, were too thin/shallow, too thick, too dark, too light, and every possibility in between. While guidelines may produce a qualified substrate for the region, knowledge about their application to various roof deck slopes, drainage designs, watering and applications of different plant forms to rooftop microclimates is essential.

Advertisement

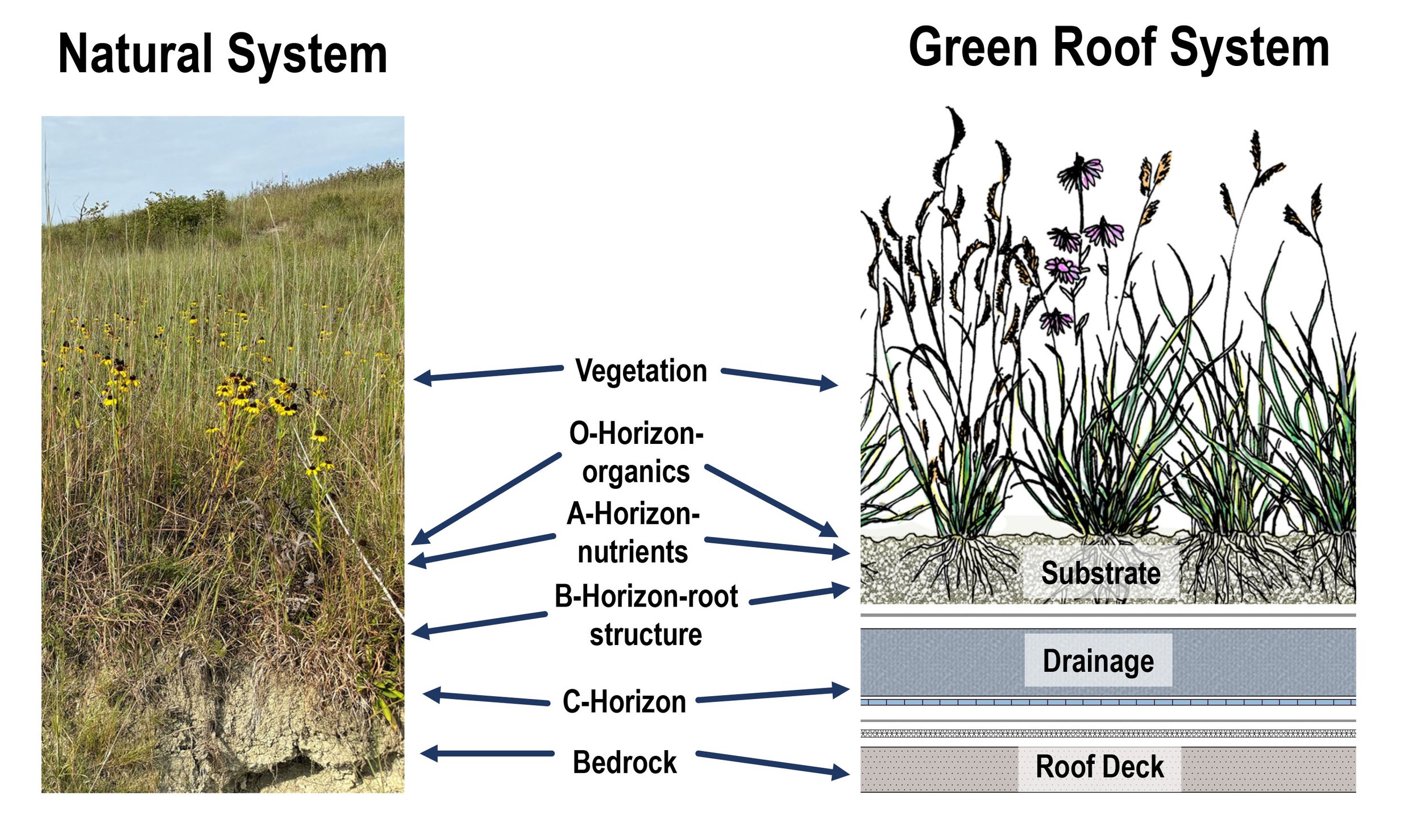

Diagram of key functional roles of natural and fabricated systems provided with green roof systems. Bruce Dvorak

The beauty of a guideline is that it is a place to begin a conversation with local experts. The innovation of guidelines is that they guide decisions on public infrastructure where construction bidding requires generic characterization of the substrate. They are also essential to developing substrates in new markets.

The upshot is that there are many venues for learning about substrates and how to apply knowledge and interpretation of guidelines. It is recommended that anyone interested in learning to design green roofs to team up with local experts, attend green roof conferences, and/or invest in green roof training or continuing education.

Industry Substrate Innovations

While guidelines aim for the consideration of substrate materials and characteristics, industry innovations can push the boundaries of well-accepted norms, beyond common standards and agreements, and can lead to guideline revisions. Sometimes these innovations make huge strides forward for green roofs. However, claims of substrate innovations that are not proven through testing and pilot projects, should be considered experimental. Successful innovations require much testing and trials over years and in different applications to see how they perform.

Aside from the well-known use of expanded shale, slate, or clay in substrates, recycled or waste materials have been incorporated into substrates, including clay and sewage sludge, paper ash, and carbonated limestone, conifer bark, (Molineux, Fentiman et al. 2009). Additionally, tire crumbs, zeolite, Biochar, volcanic ash, pumice, scoria, crushed brick or roof tiles, plastics, glass, rockwool, and many more elements have been trialed (Ampim, Sloan et al. 2010, Cao, Farrell et al. 2014, Kader, Chadalavada et al. 2022).

Brown or rubble roofs explore substrates made entirely from found materials or crushed materials such as bricks found on the site. Rubble roofs can be seeded to help establish vegetation or left to natural succession. These are not typical of what most developers see or know about green roofs. There are many proven projects where this approach is a good alignment, especially in Europe, and for the support of biodiversity (Grant 2007, Brenneisen 2012, Nash, Ciupala et al. 2019).

Green roof vegetation on the Omni Ecosystems Headquarters in downtown Chicago, Illinois. Hundreds of taxa of plants are trialed on this roof, including native and exotic herbs. Photo Bruce Dvorak September 2024

For example, one approach is to minimize the weight of the media and maximize the nutrient and microbial life of the media. Omni Ecosystems achieved both with their Omni Infinity Media®, which consists of two substrate layers, a lightweight base layer called GEO consisting of expanded perlite and a nutrient-packed growing layer called BIO containing over 1,500 species of microbes. The two layers provide everything plants need to begin growing, sustain growth, and reproduce while providing over 76% total pore space for enhanced stormwater retention. Innovations such as these are needed to explore how substrates can be applied to roof decks with limited weight capacity.

The day I visited the Omni Ecosystems headquarters in Chicago, I learned how the substrate layers are manufactured locally in many locations across the United States and are delivered in large bags that are easily lifted to rooftops for spreading. Their headquarters building sports a green roof constructed with their media in depths ranging from 4 inches to 30 inches deep. That green roof assembly is designed to add only an average 20 to 60 pounds per square foot when fully saturated to the pre-existing roof deck. All of the vegetation was healthy and had maximum coverage of the substrate. To date, Omni Infinity Media has established over 1,000 taxa of plants on green roofs across North America. Omni Ecosystems provides installation instructions, maintenance guidelines, and quarterly updated product data (all informed by FLL guidelines and ASTM standards) available on its website.

Without microbial life established in the substrate, green roof vegetation can struggle to establish. Some blenders deliver growing media that is sterile, with little or no microbial life. Providing a substrate blend that is installed with microorganisms, or with additives jump-starts plant growth and helps suppress invasive vegetation from taking hold.

There are many providers of substrates that offer their own suite of substrate designs. When selecting a substrate, it is important to understand the standards and expectations of substrate performance many years beyond installation. It is important to visit case examples of projects with unique blends. Claims made by providers of innovative substrates should be verified, with quality assurances regarding how the media is expected to perform over decades. While industry innovation is important, it is also important to have confidence that the substrate will perform and endure.

Research and Performance

A final word about substrates is in regard to performance. One of the strengths of substrates that meet the characteristics of the FLL green roof guidelines is that in Germany, inspections, or testing of substrates is common with post-installation inspections. The vegetation is expected to cover at least 80 percent of the substrate after two years. In the early days of green roof research in North America, much of the peer-reviewed research on green roofs was regarding substrates (Thuring, Berghage et al. 2010, Best, Swadek et al. 2015). All of the key elements of substrates needed to be investigated before green roof designers could design, plant and maintain green roofs with confidence or expand into regions with challenging climates (Decker, et al. 2022 , Sutton 2008, Schneider, Fusco et al. 2014, Klein and Coffman 2015). Today, with new industry innovations taking place, research regarding the performance of new substrates and new green roof products is equally important.

Summary

This article reviewed three domains where innovation has been facilitating the support of planting green roofs. Guidelines help designers make decisions and select parameters for substrates from which plants will grow and rejuvenate for the life of the green roof. Industry innovations expand what is known about typical applications of green roofs and help expand green roofs into new markets. Research on green roof substrates helps report on explorations and trials that consider substrate variables.

Advertisement

Bruce Dvorak, FASLA, is a Professor at Texas A&M University in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, where he has been conducting green roof and living wall research since 2009. Bruce is the chair of the GRHC Research Committee and founded a new Regional Academic Center of Excellence in 2022, the Southern Plains Living Architecture Center. Bruce received the GRHC Research Award of Excellence in 2017 and teaches green roofs and living walls in his courses in landscape architecture programs at Texas A&M University. His edited book, Ecoregional Green Roofs: Theory and Application in the Western USA and Canada (2021) provided inspiration and content for this article.

To learn about green roof design to support biodiversity, see the Living Architecture Academy Course: Case Studies of Biodiverse Green Roofs, by Bruce Dvorak.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank John Hart Asher, Michael Davenport Davenport and Molly Meyer for sharing their knowledge about the green roofs they designed. Thank you also to rooflite® Tecta America® Bioroof® and Emory Knoll Nursery for their support of green roof research at Texas A&M University.

References

Ampim, P. A., J. J. Sloan, R. I. Cabrera, D. A. Harp and F. H. Jaber (2010). "Green roof growing substrates: types, ingredients, composition and properties." Journal of Environmental Horticulture 28(4): 244-252.

ASTM E2777 14 (2014). Standard Guide for Vegetative (Green) Roof Systems: 14.

ASTM E 2400 (2006). Standard Guide for Selection, Installation, and Maintenance of Plants for Green Roof Systems. West Conshohochen, PA, ASTM International: 4.

Best, B. B., R. K. Swadek and T. L. Burgess (2015). Soil-based green roofs. Green Roof Ecosystems, Springer: 139-174.

Brenneisen, S. (2012). Green roofs - Key factors in habitat design: substrates, light weight solutions, species groups and diversity. International Scientific Meeting for Green Roof Research Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services, Helsinki, Finland.

Cao, C. T., C. Farrell, P. E. Kristiansen and J. P. Rayner (2014). "Biochar makes green roof substrates lighter and improves water supply to plants." Ecological Engineering 71: 368-374.

Carson, R. (1962). Silent Spring. Boston, MA, Houghton Mifflin.

Catalano, C., V. A. Laudicina, L. Badalucco and R. Guarino (2018). "Some European green roof norms and guidelines through the lens of biodiversity: Do ecoregions and plant traits also matter?" Ecological Engineering 115: 15-26.

Decker, Allyssa, Lee R. Skabelund, Yuting Gao, and Priyasha Shrestha, Investigating Extensive Green Roof Native Plant Growth Over A Four-Year Period In The Central Great Plains, Cities Alive conference Philadelphia, PA, Oct. 2022.

Dvorak, B. (2011). "Comparative analysis of green roof guidelines and standards in Europe and North America." Journal of Green building 6(2): 170-191.

Dvorak, B. and T. Woodfin (2023). Seeding Green Roofs with Regional Vegetation in the Southern Plains. Green Infrastructure Research Symposium, Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, Virtual, Green Roofs for Healthy Cities.

FLL (2002). Guideline for the Planning, execution and Upkeep of Green-roof sites, Forschungsgesellschaft Landschaftsentwicklung Landschaftsbau e. V.

General Services Administration (2011). The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings: A Report of the United States General Services Administration. Washington, D.C., United States General Services Adminstration: 152.

Grant, G. (2007). "Extensive Green Roofs in London." Urban Habitats 4(1): 1541-7115.

Kader, S., S. Chadalavada, L. Jaufer, V. Spalevic and B. Dudic (2022). "Green roof substrates—A literature review." Frontiers in Built Environment 8: 1019362.

Kaiser, D., M. Köhler, M. Schmidt and F. Wolff (2019). "Increasing evapotranspiration on extensive green roofs by changing substrate depths, construction, and additional irrigation." Buildings 9(7): 173.

Klein, P. M. and R. Coffman (2015). "Establishment and performance of an experimental green roof under extreme climatic conditions." Science of the total environment 512: 82-93.

Leopold, A. (1966). A Sand County Almanac: with Essays on Conservation from Round River. United States of America, Oxford University Press, Inc.

Mahdiyar, A., S. Tabatabaee, K. Yahya and S. R. Mohandes (2021). "A probabilistic financial feasibility study on green roof installation from the private and social perspectives." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 58: 126893.

Molineux, C. J., C. H. Fentiman and A. C. Gange (2009). "Characterising alternative recycled waste materials for use as green roof growing media in the UK." Ecological Engineering 35(10): 1507-1513.

Nash, C., A. Ciupala, D. Gedge, R. Lindsay and S. Connop (2019). "An ecomimicry design approach for extensive green roofs." Journal of Living Architecture 6(1): 62-81.

Philippi, P. M. (2005). Introduction To The German FLL-Guideline For The Planning, Execution and Upkeep of Green Roof Sites. The Third Annual Greening Rooftops for Sustainable Communities Conference.

Schneider, A., M. Fusco and J. Bousselot (2014). "Observations on the survival of 112 plant taxa on a green roof in a semi-arid climate." Journal of Living Architecture 1(5): 10-30.

Shahmohammad, M., M. Hosseinzadeh, B. Dvorak, F. Bordbar, H. Shahmohammadmirab and N. Aghamohammadi (2022). "Sustainable green roofs: a comprehensive review of influential factors." Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29(52): 78228-78254.

Sutton, R. K. (2008). "Media modifications for native plant asemblages on extensive green roofs."

Thuring, C. E., R. D. Berghage and D. J. Beattie (2010). "Green roof plant responses to different substrate types and depths under various drought conditions." HortTechnology 20(2): 395-401.