Sky-High Sustainability: The Long-Term Success of Toronto’s Green Roofs

Advertisement

Introduction

Green roofs, as a nature-based solution, are increasingly developed in cities on a global scale to improve much needed ecosystem services. They help reduce urban flooding, improve water quality, mitigate heat island effects, and provide additional socioeconomic benefits (1). Due to the multifunctionality and benefits of green roofs, more than 100 cities across the world have established policies and/or incentive programs to encourage green roof development (2).

Figure 1. Aerial image of a green roof with multiple units at the rooftop of the University of Toronto. Photo: Wenxi Liao.

Toronto was an early adopter of green roofs in North America, and due to the Green Roof Bylaw, enacted between 2009 and 2025, over 1,200 green roofs were installed between 2010 and 2025. Despite this rapid growth, very little is known about the long-term performance of these roofs. Each year, the city of Toronto collects very high-resolution multispectral images of the city. These images, when processed, can be used to remotely assess plant health.

Studying ‘Greenness’ From the Sky

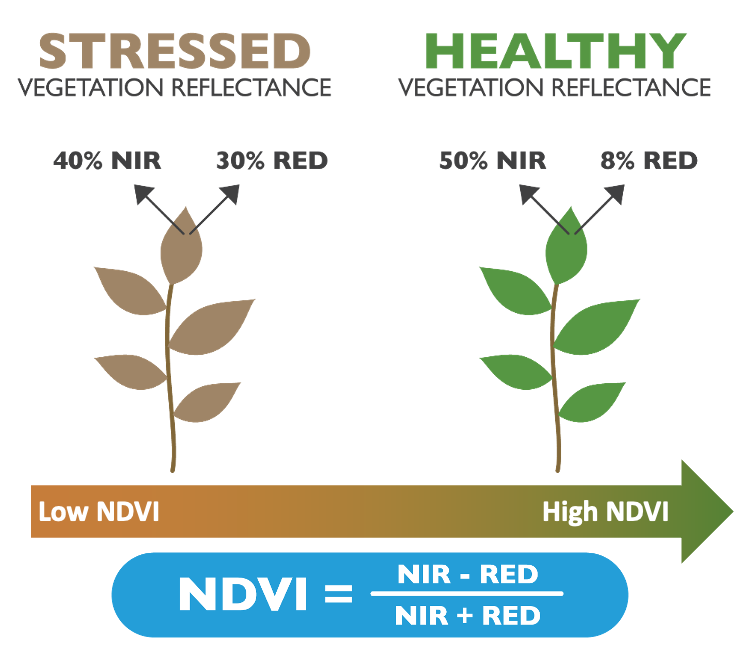

Plant health is crucial for providing ecosystem services. Healthy plants can help improve water quality, mitigate urban flooding, and provide cooling effects. In the field of remote sensing, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is used as a plant health indicator. This metric quantifies how plants reflect red (visible) and near-red (non-visible) light. Chlorophyll absorbs visible light, and so images with high NDVI values are associated with lush, healthy and green cover, while images with low NDVI values are associated with sparse, stressed and poor vegetation cover.

Advertisement

Figure 2. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), a commonly used indicator of vegetation health. Image adapted from AGRICOLUS.

In our study published in Nature Cities in 2025, we analyzed orthoimages of 1,380 green roof units across the City of Toronto from 2011 to 2018 to examine how plants and their ‘greenness’ changed over time. We then compared NDVI values with roof characteristics, including the size of the roof system, the height of the building, plant type (sedum mat, grass, woody plants, and a mix of grass and woody plants), and the aspect ratio of the green roof (i.e., how elongated is the roof system) to identify building characteristics that are associated with healthy and green roofs over the long term.

Long-term Plant Health and Patchiness on Green Roofs

Figure 3. An example of a green roof that shows temporal increase trend during the growing seasons.

We were excited to discover that plant health on both intensive green roofs (those with deeper substrate and typically woody plants) and extensive green roofs (typically planted in a shallow substrate with sedum and grasses) in Toronto improved with age, with less than 5% of those examined showing a decline. Along with this increase in plant health, we observed a reduced vegetation patchiness over time, indicating that green roofs become more uniformly vegetated as they mature. In particular, sedum mat systems showed notable improvement, likely due to the strong drought tolerance and resilience of sedum species such as Sedum Phedimus, and related genera. These findings demonstrate that vegetation on green roofs in Toronto is healthy, resilient, and long-lasting.

Effects of Roof Characteristics on Green Roof Vegetation Health

We observed that several roof characteristics, particularly the size of the green roof unit, the height of the building, and the type of vegetation, play important roles in determining plant health. Larger green roof units tend to support healthier vegetation. This is likely because plants in larger roof units are less affected by edge conditions, where the environment is typically harsher due to greater exposure to strong wind, variable temperature and moisture (6, 7). Thus, the larger roof areas create a more stable microclimate within the systems that support plant growth.

Advertisement

Figure 4. Blooming plants on urban green roofs. Photo: Liat Margolis.

In contrast, plant health tends to decline on taller buildings. Plants on taller buildings often experience stronger winds and more turbulent conditions, which can stress vegetation and reduce overall plant performance (8). Overall, our findings suggest that larger green roof systems are needed to maintain healthy vegetation on high-rise buildings (those with a height above 20 meters). The larger roof systems can enhance the microclimate within the planted area, buffering plants from harsh edge conditions and offsetting some of the negative impacts associated with height. Overall, plants on extensive green roofs were healthier than those on intensive roof systems, with sedum mats outperforming woody plants and grasses due to the strong drought tolerance and resilience.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrate that vegetation health on green roofs generally improves over time. We also identify several key factors, including the size of the green roof unit, the building height, and the type of vegetation, that strongly influence plant performance. These insights offer valuable guidance for planners, designers, and policymakers aiming to enhance the effectiveness, resilience, and long-term sustainability of green roofs in urban environments.

This study also demonstrates an efficient, scalable method for assessing vegetation health across large numbers of green roofs, and it can be applied to many types of green infrastructure in cities worldwide.

For more details, please read the work published in Nature Cities: https://rdcu.be/eRAkK

Advertisement

Wenxi Liao is an Assistant Professor at the University of Guelph.

Jennifer Drake is an Associate Professor at Carleton University and a Canada Research Chair in Stormwater and Low Impact Development (Tier II).

Acknowledgements

Research study co-authors included Wenxi Liao, Madison Appleby, Howard Rosenblat, Md. Abdul Halim, Cheryl A. Rogers, Jing M. Chen, Liat Margolis, Jennifer A. P. Drake, Sean C. Thomas. This study was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and School of Cities. This work was also funded by a Schwartz Reisman Fellowship to W.L. We thank S. Herda, A. Smith, A. Collia, G. Frizzi, University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) Facility team and UTSC EHS team for assistance with data collection and Map and Data Library and City of Toronto for providing the data and relevant information.

References

1. G. Mihalakakou, et al., Green roofs as a nature-based solution for improving urban sustainability: progress and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 180, 113306 (2023).

2. T. Liberalesso, C. Oliveira Cruz, C. Matos Silva, M. Manso, Green infrastructure and public policies: an international review of green roofs and green walls incentives. Land Use Policy 96, 104693 (2020).

3. City of Toronto, Toronto Municipal Code Chapter 492: Green Roofs. (2017).

4. City of Toronto, Eco-Roof Incentive Program. Eco-Roof Incentive Program. Available at: https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/water-environment/environmental-grants-incentives/green-your-roof/.

5. City of Toronto, City of Toronto Green Roof Bylaw. City of Toronto Green Roof Bylaw. Available at: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/planning-development/official-plan-guidelines/green-roofs/green-roof-bylaw/.

6. R. M. Ewers, C. Banks-Leite, Fragmentation impairs the microclimate buffering effect of tropical forests. PLoS ONE 8, e58093 (2013).

7. L. F. S. Magnago, M. F. Rocha, L. Meyer, S. V. Martins, J. A. A. Meira-Neto, Microclimatic conditions at forest edges have significant impacts on vegetation structure in large Atlantic forest fragments. Biodivers Conserv 24, 2305–2318 (2015).

8. D. M. Jani, W. M. N. W. Mohd, S. A. Salleh, Effects of high-rise residential building shape and height on the urban microclimate in a tropical region. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 767, 012031 (2021).

9. O. Starry, J. D. Lea-Cox, J. Kim, M. W. van Iersel, Photosynthesis and water use by two Sedum species in green roof substrate. Environ. Exp. Bot. 107, 105–112 (2014).

Article citation: Liao, W., Appleby, M., Rosenblat, H. et al. Remote sensing for healthy vegetation on green roofs. Nat Cities 2, 990–999 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00331-w