Planting Living Roofs for Native Pollinators (Part I: Sedums)

Advertisement

Biodiversity was late to develop across North American landscapes. Up until 10,000 years ago, much of the northern half of North America was largely covered in ice and snow. There was a pattern of continental ice sheets advancing and retreating across North America for the past 2.4 million years, acting like a giant biodiversity “eraser” leaving little but arid deserts in the path of glacial activity. During the Pleistocene Epoch, in the mountainous west, sky islands rose above continental ice fields where mountain peaks formed refugia where some flora and fauna took advantage of the rocky real-estate (Shafer, Cullingham et al. 2010). Although the cultural landscapes we live and build upon today were once buried under miles thick of ice and snow, some of the same plants we find across the west today survived and developed unique relationships with pollinators on these sky islands, including plants appropriate for living roofs. Some geneticists believe that one of the effects of habitat sky islands was concentrated genetic populations of pollinators where these isolated patches resided, and unique mutual benefits developed (DeChaine and Martin 2005).

While the flora and fauna of North American landscapes took millennia to develop, within the past one hundred years humans have succeeded in wiping a human-made “eraser” on the land, eradicating biodiversity much like the glaciers did. In urban environments, however, where buildings, pavements, and cultural landscapes now cover the land, there is one ecological intervention that does not compete with the ever-increasing price of land—living roofs. Living roofs can recover space for pollinators in dense urban environments, where native ecosystems once persisted. This article is the first of several that will focus on the unique role of living roofs made for the preservation of native pollinators.

Sedum is one of the most popular genera for use on shallow depth green roofs. More than a few native sedums have developed special relationships with native pollinators. This article features several sedums for use on living roofs to help support pollinators through the planting of green roofs with plants they need to survive. Future articles will cover how grasses, forbs, and other succulents serve pollinators.

Sedum lanceolatum grows in a large patch (left) on the foothills of the Rocky Mountains at the Vedauwoo Recreation, part of the Medicine Bow National Forest. Sedum lanceolatum (right) grows 32 kilomters away on a semi-intensive green roof at the Berry Biodiversity Center in Laramie, Wyoming (Dvorak and Bousselot 2021). Photos: Bruce Dvorak, June 18, 2018.

The Rocky Mountain Parnassian is a butterfly that is partial to Sedum lanceolatum. This butterfly uses Sedum lanceolatum exclusively to feed upon during the larval stage, and as an adult. Males are highly mobile as they seek patches of the plant to feed off nectar during the summer when the plant is in bloom. Sedum lanceolatum grows in all states of western US and Canada in elevations from moderate to high elevations on rocky-sloped environments west of Nebraska. It also grows well on green roofs where the substrate is appropriately drained. Sedum lanceolatum serves many species of butterflies and moths, as there are three known taxa in California that use it including the Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta Claudia, Callophrys mossii Moss' Elfin, Callophrys mossii, Rocky Mountain Parnassian Parnassius smintheus, and five additional taxa suspected to make use it (Junonia coenia, Callophrys augustinus, Callophrys fotis, Parnassius behrii, and Arctia caja).

Advertisement

In South-central and Midwest U.S. states, the native Sedum pulchellum grows on shallow soils found near rocky outcrops, limestone glades, and other sunny well-drained environments. Sedum pulchellum is a high producer of pollen and attracts native bees such as Andrena and a soldier fly (Nemotelus bruesii). Sedum puchellum is considered one of the top native sedums to include in mixes in the central portions of North America. Other sedums such as Sedum kamtschaticum and Sedum album are now naturalized to North America, but not indigenous and both perform well on living roofs and attract butterflies and bees.

While Sedum Pulchellum has faired well on green roofs, including some shady green roofs (Getter, Rowe et al. 2009), not all native sedums have a strong track record of success. Sedum ternatum, is native to wooded and shady environments and has not competed well on open sunny green roofs trials in the Midwest (Hawke 2015). Just because a plant is native, does not mean that it will survive on living roofs, especially if it is planted on a living roof where its microclimate is too different from its natural setting.

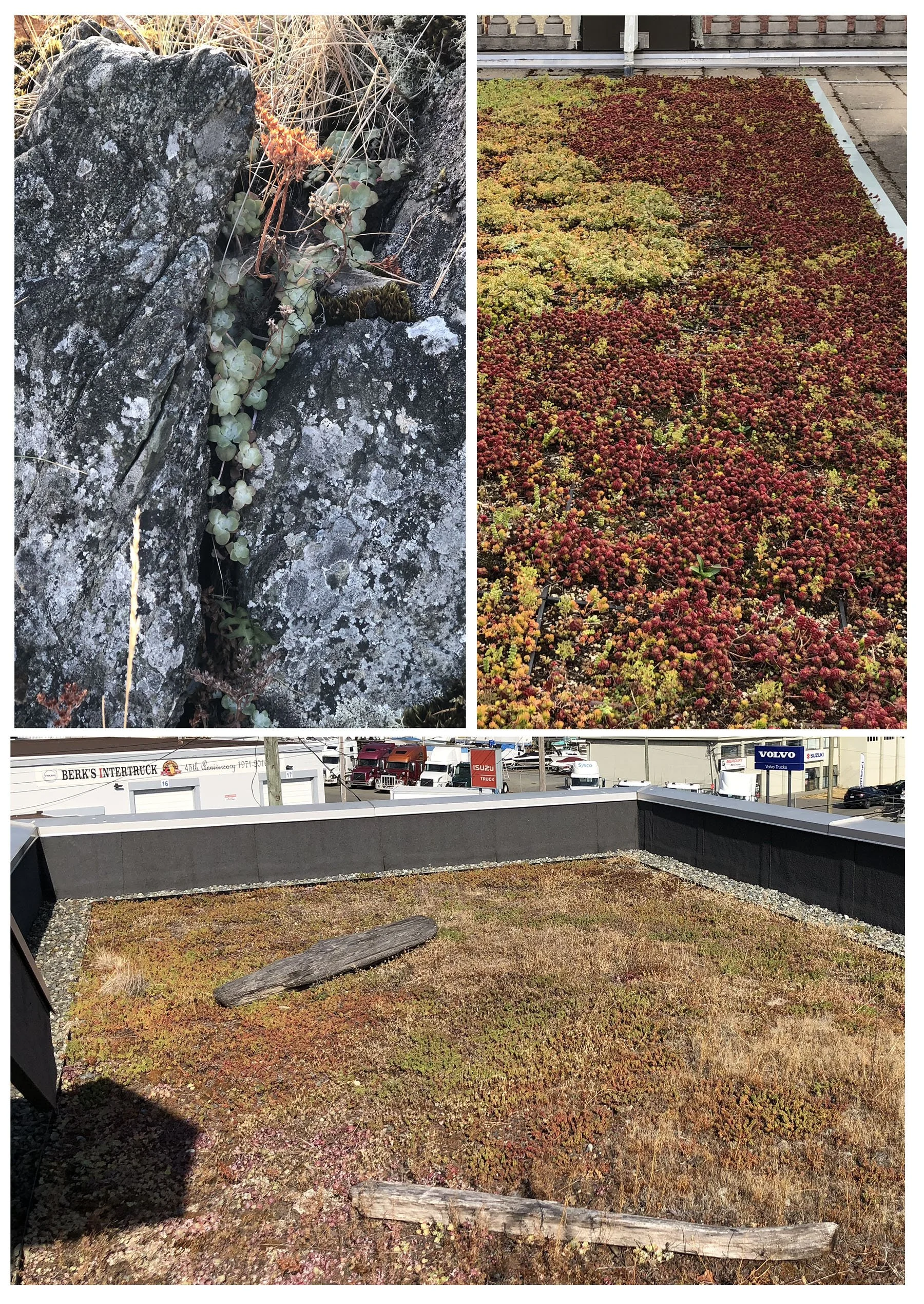

Sedum spathulifolium is native to the western side of the Pacific Mountain ranges from British Columbia to the U.S. Mexico border. It is native to well-drained environments, rocky slopes from sea level to lower elevations of foothills. It serves bees, butterflies and is a larval plant. It is also a host plant for the endangered San Bruno Elfin butterfly (Callophrys mossii bayensis). The Elfin uses only Pacific Stonecrop (Sedum spathulifolium) plants to complete its life cycle. Many living roofs along the Pacific coast support Sedum spathulifolium on extensive type green roofs (Dvorak and Drennan 2021, Dvorak and Roehr 2021, Dvorak and Rottle 2021, Dvorak and Starry 2021). Other butterflies that may use this sedum are Moss' Elfin (Callophrys mossii), Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia), Variegated Fritillary (Euptoieta Claudia), The Brown Elfin (Callophrys augustinus), Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius smintheus), Desert Elfin (Callophrys fotis), Sierra Nevada (Parnassian Parnassi).

Sedum spathulifolium growing in its native habitat of rocky shallow soils at Pipers Lagoon Park in Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada (top left), also growing only several kilometers away on the Island West Development head office green roof (bottom) in Nanaimo, and over 500 kilometers away growing on the ecoroof on the Multnomah County's Central Library in Portland, Oregon as a cultivated form Sedum spathulifolium 'Purpureum'. On both living roofs, Sedum spathulifolium is mixed in with other sedums. See also the Fall issue of LAM to learn about how Sedum spathulifolium was planted to provide habitat for the Federally endangered San Bruno Elfin butterfly. Photos: Bruce Dvorak, August 2018.

Advertisement

Sedum divergens grows on the ecoroof at the of the Multnomah County's Central Library in Portland, Oregon (Dvorak and Starry 2021) . This resilient species endures drought events and supports butterflies such as the alpine butterfly (Parnassius smintheus) where climate change may affect its territorial habitat (Filazzola, Matter et al. 2020). Living roofs could help support pollinators that are dependent on diverse roofs that include native vegetation. Photos courtesy Bruce Dvorak, September 2018.

Sedum divergens and Sedum oreganum also grow widespread across the Pacific Coast and attract pollinators some of the same butterflies as S. spathulifolium include Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia), Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia), Rocky Mountain Parnassian (Parnassius smintheus), Moss' Elfin (Callophrys mossii) and the Desert Elfin (Callophrys fotis). Many of these butterflies live across the west and the southern United States. So, living roofs should be planted with native sedums where possible to amplify ecosystem services with vegetation from the region.

In summary, although introduced (exotic) species of Sedum are very commonly used on green roofs across North America, there are native sedums that can be worked into a diverse mix of plants to better serve native pollinators. In this first part, I covered some common native sedum and make an argument for their use because:

Three Sedum species- S. oreganum, S. spathulifolium, and S. divergens grow together at the Shq’athut - A Gathering Place, a student center for indigenous peoples on a shallow extensive living roof at Vancouver Island University. Shown here at the end of the growing season. Photo Bruce Dvorak, September 2018

Some wildlife has developed life-cycle dependency with native sedums in North America. The land area that supports the natural habitats of these pollinators is shrinking due to development practices that don’t preserve natural habitats.

There are more than a few native sedums that thrive on green roofs in North America. Ecoregional vegetation is recommended with the support of local expertise to select vegetation to support pollinators.

Biodiverse living roofs can behave like sky islands to host native pollinators when designers, growers, and installers make the microclimate of a living roof appropriate for the growing conditions of sedums

Diverse living roofs are more biologically productive and offer more choices for pollinators than low diverse roofs

Bruce Dvorak is an Associate Professor at Texas A&M University in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, where he has been conducting green roof and living wall research since 2009. Prior to his academic career, Bruce was involved with the design and management of several recognized green roofs including the Chicago City Hall Pilot Project and the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum green roofs and green wall (with Conservation Design Forum). Bruce is currently a member of the GRHC Research Committee, and received the GRHC Research Award of Excellence in 2017. Bruce teaches green roofs and living walls in his courses in landscape architecture programs at Texas A&M University.

References

DeChaine, E. G. and A. P. Martin (2005). "Marked genetic divergence among sky island populations of Sedum lanceolatum (Crassulaceae) in the Rocky Mountains." American Journal of Botany 92(3): 477-486.

Dvorak, B. and J. Bousselot (2021). Green Roofs in Shortgrass Prairie Ecoregions. Ecoregional Green Roofs: Theory and Application in the Western USA and Canada. B. Dvorak. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 143-200.

Dvorak, B. and P. Drennan (2021). Green Roofs in California Coastal Ecoregions. Ecoregional Green Roofs: Theory and Application in the Western USA and Canada. B. Dvorak. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 315-389.

Dvorak, B. and D. Roehr (2021). Green Roofs in Fraser Lowland and Vancouver Island Ecoregions. Ecoregional Green Roofs, Springer: 507-556.

Dvorak, B. and N. D. Rottle (2021). Green Roofs in Puget Lowland Ecoregions. Ecoregional Green Roofs: Theory and Application in the Western USA and Canada. B. Dvorak. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 391-449.

Dvorak, B. and O. Starry (2021). Green Roofs in Willamette Valley Ecoregions. Ecoregional Green Roofs: Theory and Application in the Western USA and Canada. B. Dvorak. Cham, Springer International Publishing: 451-506.

Filazzola, A., S. F. Matter and J. Roland (2020). "Inclusion of trophic interactions increases the vulnerability of an alpine butterfly species to climate change." Global change biology 26(5): 2867-2877.

Getter, K. L., D. B. Rowe and B. M. Cregg (2009). "Solar radiation intensity influences extensive green roof plant communities." Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 8(4): 269-281.

Hawke, R. (2015). "An evaluation study of plants for use on green roofs." Plant Evaluation Notes 38(1): 1-22.

Shafer, A. B., C. I. Cullingham, S. D. Cote and D. W. Coltman (2010). "Of glaciers and refugia: a decade of study sheds new light on the phylogeography of northwestern North America." Molecular ecology 19(21): 4589-4621.