What is a Biodiverse Green Roof?

Advertisement

Biodiversity should not be viewed as a project afterthought but should be at the forefront of all city and project planning. Apart from being vital for our survival as a species, biodiversity also supports business worth €40 trillion ($42.2 trillion US), representing half of the global Gross Domestic Product (European Commission, 2020). So how do we expand on total net urban biodiversity in the fastest way possible?

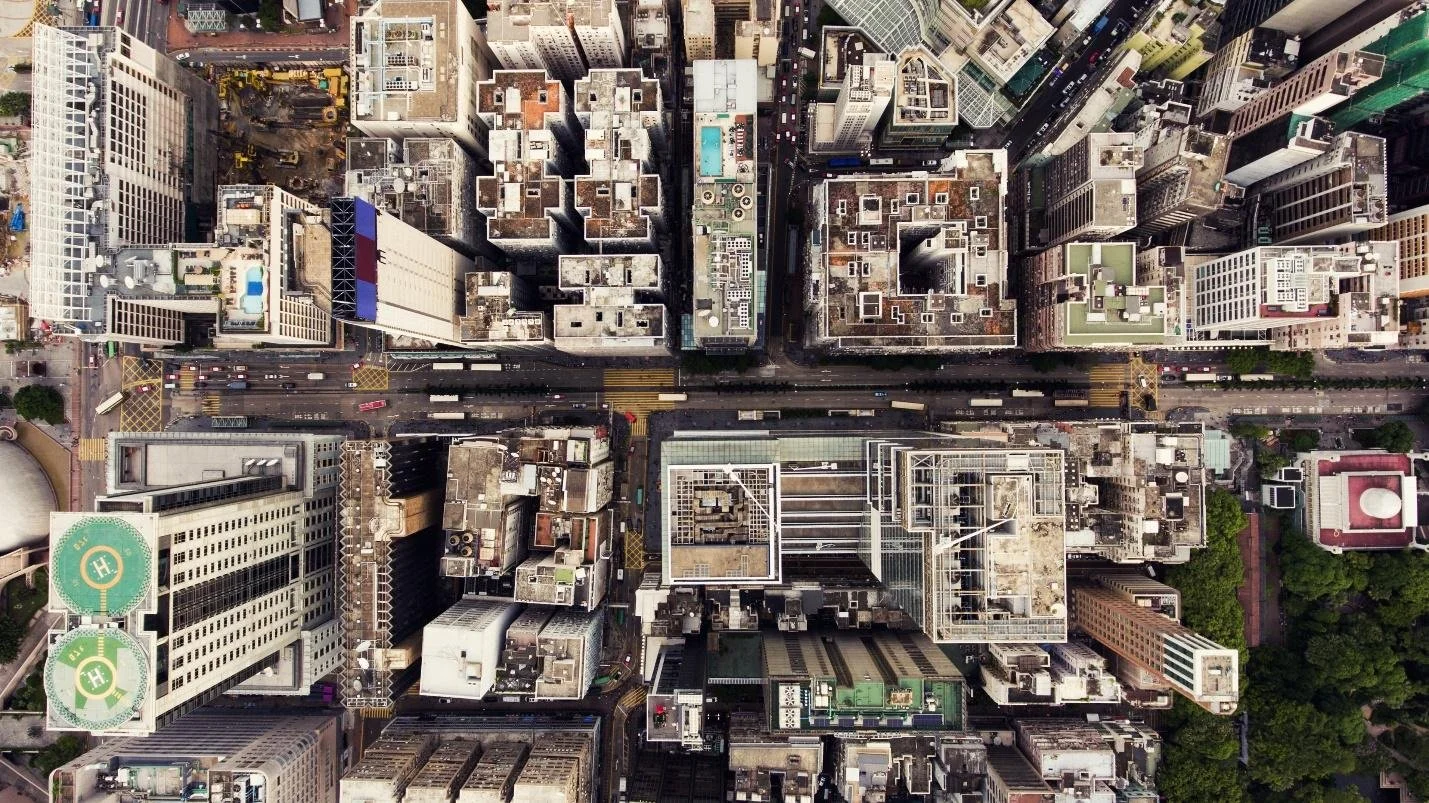

Different roof types in a city - Roof space is a missed opportunity when not greened.

Green roofs should be as biodiverse as possible given project constraints. Though perhaps controversially, I think that we can gain higher net biodiversity by expanding our definitions of what encompasses a biodiverse green roof. I sometimes worry that an almost too strict view of the definition of a biodiverse green roof can be damaging for the task at hand as an all-or-nothing mentality can result in fewer green roofs being built, and so the net total urban biodiversity might suffer.

In the end, a low biodiverse green roof is infinitely better than no green roof. A deeper, diverse, species-rich green roof is even better, but not always practical. Our best path is often to green as much as possible, and then seize as many opportunities as we can to add greater biodiversity.

Are Green Roofs Natural Spaces?

Green roofs are not genuine natural spaces. In nature, you do not find a relatively thin profile of manufactured lightweight soil with low capillary capacity. The profile of extensive green roof is often less than 10cm (4”) deep and has a drainage layer underneath the system, allowing excess water to fall out of the profiles, which is in stark contrast with garden soils, where water will take weeks to percolate into deep cavities, often 1.5-3m (5-10 ft) deep. There it remains accessible to many common plants which can access this water reservoir during droughts. Since many species of plants suck water out of up the upper layer with their deep root systems, water will automatically be drawn upwards. This aquifer-type reservoir system can supply plants with water for weeks and weeks thereby bridging droughts.

Also, the final biodiversity outcome of a green roof depends on planting time, which might favor certain plants over others. It also depends on the next season: is it wet or dry, cold, or hot? It may also depend on extreme stress levels that reduce or even eliminate several species allowing others to overtake them. It further depends on maintenance: did they fertilize, and with what? Have they added new species? And it can depend on the impact of micro-climates such as the heat reflection of walls and windows, wind tunnels, shade, you name it.

Overall survival on a green roof is determined by the level of tolerance for temperature (too hot or too cold); water (too little or too much); and light (sunny or shadey). Plants that can tolerate these extremes the best will often survive on a green roof. For these reasons, there are, of course, more possibilities for higher amounts of biodiversity on intensive vs. extensive green roofs.

Advertisement

Example of loads on an extensive green roof

Green Roof Biodiversity and Accessibility

Example of loads on an intensive green roof

In an optimal world, almost every urban rooftop is a highly biodiverse green roof. However, there are many hurdles to pass for this to happen. Often, you will need thicker substrate layers to host high plant biodiversity, which brings with it higher (weight) loads. Some grasses can survive on thinner substrates, but in many cases, their use can be limited by fire regulations, such is the case in some areas of the US. Not every project can take the cost of that extra load as additional load-bearing structures may have to be built. This is often the case for projects in lower-income areas and retrofits. This is extremely unfortunate as there already is a clear social divide in terms of access to the ecosystem services provided by urban greening.

There are, of course, beautiful examples of biodiverse roofs in low-income areas but they are often more of an exception than a rule. Plenty of data shows a clear divide between the green infrastructure “haves” vs. the “have nots.”

Different Roof Areas Can Support Different Types of Roofs

Not only do projects vary in how they can handle loads, but the project roof area is rarely homogenous, often being comprised of subsections with various load requirements and various degrees of cover e.g., HVAC equipment, paved areas, and fire requirements such as graveled fire breaks/paths. Due to this, it can be beneficial to use different green roof profiles on the different roofs on the same project. This has been shown to support greater biodiversity for both insects and plants. Sometimes, a thin sedum profile is the most optimal solution, and sometimes, a blue-green roof garden can be installed overflowing with various lush plants.

Advertisement

Recent research also suggests that one of the main limitations of using green roofs as a conservation measure is their scarcity, indicating that perhaps we are limiting ourselves by trying to achieve only deep intensive biodiverse plantings instead of mixing it up and speeding up the process?

What About the Rest of the City?

Something often missing in the discussion about biodiversity is the state of the rest of the surrounding urban area. With the risk of presenting whataboutism arguments, I would like to take a stab at the biodiversity deserts we call lawns: manicured, fertilized, irrigated, and single species.

About a year ago, we had a meeting in Montgomery County, Maryland, and were told that 28% of the entire county was covered in mowed/maintained non-agricultural grass. This translates into 370 square km (142 square miles) of grass or lawn. As a comparison, there was 0.18 square km (0.07 square miles) of green roofs. These numbers might look very different in other places outside the US, but these are still numbers we need to take to heart. Imagine if a portion of these lawns were turned into low-maintenance urban meadows with local flora – what a win.

Restoring urban meadows are low hanging fruit for biodiversity improvement in cities.

I am not saying we should scrap highly biodiverse green roofs; most certainly not. I think that should always be our goal. But I also want recognize that these 0.07 square miles of green roofs might suddenly become 28% in the future. What I am hoping for is a more diverse green roof landscape that allows for different solutions for different places and buildings. We already have some of that diversity, but sometimes the industry appears to forget about also making clear business cases for green roofs built to provide certain specific ecosystem services, such as stormwater management or energy. Sound business cases for green roofs that solve particular client problems are, in my opinion, the main driver for fast adaptation.

It is more about getting to a minimum viable product on a city scale. We need to ensure green roofs and walls spread through cities to achieve green corridors. We also need to connect them with the parks and work hard with the people on the ground to push for legal changes allowing for urban meadows (these are outlawed in many US cities). We need more system-based thinking.

Advertisement

Water and Irrigation

Water is life. Green roofs depend on access to the right amount of water at the right time to survive. What this amount and time are, is a matter of where you live and what type of green roof you have chosen. Very biodiverse green roofs tend to have much higher water requirements than extensive green roofs. In some places, it is easier to maintain green roof biodiversity than in other places. In the UK, for example, known for its frequent drizzles, more advanced plant blends with high evapotranspiration rates can be allowed for, whereas places like Seattle also have a lot of regular rainfall but long irksome drought periods mid-summer that often lead to substantial green roof irrigation requirements. In a perfect world, all places would have access to filtered greywater for irrigation, but this is far from the case. Also, here I believe this is the direction we should work toward, but alas, we are not there yet. We should be aware of this cost and make sure the clients are well aware of the maintenance requirements.

At least, a less biodiverse extensive green roof is more biodiverse than a bare roof and can act as a refuge. It also brings with it all the other benefits of a green roof, such as stormwater management, cooling, pollution capture, with low maintenance and irrigation requirements. It is also possible to interplant species to increase the biodiversity at a later point. Do I think blue-green roof gardens are more beautiful? Yes, sure I do.

Intensive green roof gardens not only look beautiful but also bring a range of secondary benefits.

Advertisement

The Unforgiving Green Roof Climate and Succession

Even if you start with a highly diverse roof, after a few seasons, you might find that the plant biodiversity has decreased due to natural biological succession. Over time, unless you keep a close eye on the roof, you will find that the communities have changed due to natural selection. The sturdiest plants for these particular conditions will survive. We can never assume that because a plant does well in a specific climate, it will also do well on a roof in the very same climate zone. The roof is an unforgiving environment for a plant, with strong temperature fluctuation, often high UV radiation and wind. Far from all plants do well on a green roof, but some do well in certain climatic regions.

Green roofs are not a one-size-fits-all and will never be. Different roof types solve other problems, and a roof that performs well in one climate performs poorly in another. This is also true for the plant selection.

I would love to see a rapid urban biodiversity increase, and I think the road there is to build as many green roofs as possible. Maybe not all of these green roofs are biodiversity perfect, but at least they were built. That is the main thing. We need to take a step back and view the urban ecosystem in its entirety instead of staring at single roofs. We have so preciously little time and need to act fast with all the measures we have.

Dr. Anna Zakrisson is a Swedish biologist and VP of European Affairs for Green Roof Diagnostics. She has studied and carried out research in plant sciences and microbial ecology at several renowned international institutions, including Cambridge University, UK, Max-Planck Institute, Germany, and Stockholm University, Sweden. Since 2018, she has worked as a consultant for green infrastructure and is currently based in Berlin, Germany.