The Migratory Bird’s-Eye View of Green Roofs - Designing Rooftops for Birds

Advertisement

A Migratory Blackpoll Warbler foraging for insects in New York City. This small, 5" migratory bird can migrate from as far as Nome, Alaska to Venezuela. During fall migration these birds use green space in New York City as stopover habitat to forage for insects before embarking on a 3 day, 1,800 mile flight over the Atlantic. Blackpoll Warblers have been recorded foraging near native vegetation and bird-safe glass on the Javits Center green roof during fall migration. Photo: Steve Nanz

Picture New York City. More specifically, midtown Manhattan, just a few blocks from Times Square. You are probably imagining bright lights, bustling, noisy streets, and maybe even the smell of roasting nuts or hot pretzels if you have ever visited. I think of something very different: sitting beneath an apple tree, surrounded by waist-high vegetation, watching a tiny bird with sharp black stripes, bright white cheeks, and a black cap bouncing between branches, happily foraging on small insects. This bird, a Blackpoll Warbler, arrived that morning after flying from as far away as Nome, Alaska. It's ignoring me, and the rest of the city, while it refuels on insects before taking off for a three-day flight over the Atlantic Ocean to South America. And this is all happening on top of a building, on a green roof.

One Manhattan green roof where a Blackpoll Warbler foraging is a regular sight is on top of the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, the largest green roof in New York City. We at New York City Audubon have been monitoring the Javits roof for insects, birds, and bats since 2014. The Javits Center has a network of green roofs totaling nearly eight acres planted with Sedum, a vegetable farm, a native pollinator garden, and an apple orchard, all adjacent to bird-friendly glass. It is truly a rooftop wildlife refuge, providing habitat for at least 52 bird species, five bat species, 19 native bee species, and hundreds of arthropod species. However, before a major renovation around 2012 that included the installation of the first green roofs, it was one of the biggest bird killers in New York City. Its large glass atriums killed hundreds of birds a year—an all-too-common occurrence in major cities.

Migratory Birds Are in Urban Areas, Too

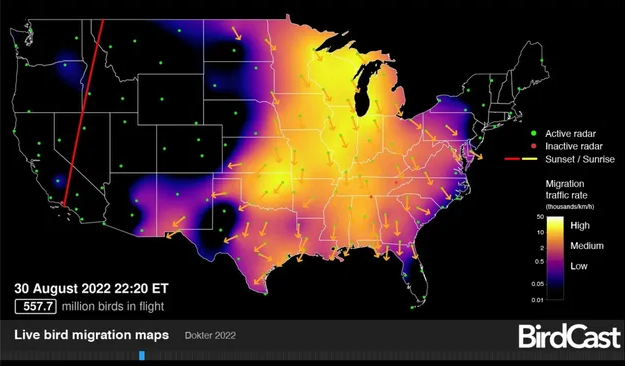

Birds migrate in the hundreds of millions each spring and fall across North America. Using weather radar, the team at BirdCast is able to track and predict the number of migratory birds traveling overhead on any given night. On August 30th, 2022, approximately 557.7 million migratory birds were flying along the Mississippi Flyway, encountering cities like Minneapolis-St. Paul, Memphis, and New Orleans, all cities where more green space is needed for migratory birds. Photo: BirdCast/Dokter 2022.

Though most New Yorkers would be surprised to see or hear about a Blackpoll Warbler in New York City, its visits are not exceptional. Rock Pigeons, House Sparrows, and European Starlings are the most obvious birds to city residents, but they are just a fraction of the total number of birds found in most cities.

Every fall and spring, billions of birds migrate across the Americas—approximately 70 percent of North America’s birds. Some, like the Blackpoll Warbler, make epic cross-continent journeys, while others, like the White-throated Sparrow, whose song is a familiar sign of spring, never leave North America.

Most of North America's migratory birds make their journey at night, and on any given night during migration hundreds of millions of birds are traveling overhead. These colorful or charismatic birds are usually found in deep hardwood forests, South American rainforests, or the sub-Arctic. But as they follow ancient flyways, they inevitably pass through cities that have been built along the way—sometimes drawn there by the glow of nighttime lights that override birds' ability to orient. City lights draw them in like moths to a flame, and they often collide with buildings.

These feats of migration require an immense amount of energy. When the sun rises and birds land for a brief daily stopover, they need lots of food, usually invertebrates, to quickly refill their fuel stores. However, birds landing in urban areas find few places to forage in the typical urban landscape of streets, sidewalks, and conventional roofs. Unless they can make it to the few parks or green spaces available, many birds are unable to sufficiently refuel. That's the gap that green roofs fill.

Advertisement

A small migratory flycatcher, an Eastern Phoebe, stopping on the Javits Center green roof to forage on aerial insects. In this fall migration photo, taken by a motion-activated trail camera deployed on the green roof as part of an NYC Audubon biodiversity study, the Eastern Phoebe has successfully captured a Muscid fly, an important fuel source that will help it continue migration south. Photo: New York City Audubon

Green Roofs Can Help Birds During Migration

Green roofs designed with biodiversity in mind can host high densities of invertebrates (in this case, bird food) in otherwise impoverished landscapes. Although green roofs cannot replace ground-level green spaces, many elements can be incorporated into a green roof's design that benefit migratory and breeding birds.

When designing green roofs for birds, it's important to select mostly native plants, if possible. Native plants have co-evolved with native invertebrates and therefore host far more invertebrates than non-native ones. Also important is a variety of habitats within a green roof—the more different habitat types, the more invertebrates, and the more birds.

Also, the size of a green roof and its context within the landscape can influence the abundance and richness of birds using it. With all other habitat elements being equal, the number of birds and diversity of species that use a green roof generally increase with its size. The surrounding landscape can also drive or limit species use. Because green roofs are often of lesser habitat quality than ground-level natural green space, a green roof adjacent to a large park with high- quality habitat may not be as beneficial for birds as a green roof isolated within the urban matrix.

Finally, one of the most important things to consider when designing a green roof is not to actively kill birds with design elements of the building!

Don’t Kill the Birds Visiting Your Roof

People love having a good view of a green roof, but the window or glass railing that allows the view is deadly to birds. Birds don't perceive glass or architectural cues like window frames or railings. They perceive a reflection of vegetation as real and fly towards it for rest or forage.

Bird collisions with glass may seem rare. Most birds that collide with glass go undiscovered—they die quietly in vegetation, get consumed by a predator, or are swept up by street cleaners. But it is a serious problem that continues to contribute to the alarming decline of birds in North America, which has lost nearly one in four birds in the last 50 years. In New York City, up to 230,000 birds die each year in window collisions. Across North America, that number can approach nearly 1 billion. If a green roof built to attract birds has unprotected adjoining windows, those windows are killing the birds it would otherwise be aiding.

Fortunately, making glass visible to birds is easy. To prevent bird-window collisions, cover glass with a pattern spaced apart by 2 inches or less—birds will try to fly through spaces larger than that. While products like single-bird decals do not work, a plethora of available products have been field-tested and are proven to reduce collisions. Bird-safe films (many of which look like small stickers) can be applied to the exterior of existing glass to prevent collisions. These films can be visible to the human eye (like Feather Friendly or Solyx) or they can be invisible to humans but visible to birds because of ultraviolet properties (Bird Divert). Glass products with built-in bird-safe properties are available and, similar to the films, can be visible or invisible to humans. Any product used to reduce collisions should have an assigned Threat Factor of 30 or less (as tested by the American Bird Conservancy). If you are interested in viewing products in person or learning more, visit us at NYCAudubon.org or our partners at the American Bird Conservancy at abcbirds.org/glass-collisions/.

Advertisement

Two examples of bird-safe films installed on the external surface of glass facades in New York City. The Feather Friendly product on the left consists of small white dots. Bird Divert, in the images on the right, consists of dots barely visible to humans but visible to all birds that can see ultraviolet light. Both installations significantly reduced bird-window collisions. Photo: Feather Friendly - New York City Audubon; Bird Divert - Melissa Breyer.

Green Roofs are Important for the Conservation of Migratory Birds

The migratory birds recorded using the Javits Center, with its diverse habitats and bird-friendly glass, are just a few of the birds using green roofs throughout North America. Green roofs can provide critical habitat for birds in urban areas when they're designed with birds in mind—both as habitat and as a safe space away from deadly glass if the glass installed is bird-friendly.

Advertisement

Dr. Dustin Partridge is the Director of Conservation and Science at NYC Audubon, where he leads the organization's conservation science initiatives, all of which aim to protect wild birds and their habitats in New York City for all New Yorkers. He is also the Managing Director of the Green Roof Researchers Alliance, a consortium of over 80 researchers, educators, and policymakers from 25 different institutions, and an Adjunct Professor at Columbia University. Dr. Partridge has over a decade of research experience focused on urban ecological dynamics and the conservation value of human-built habitats, such as green roofs and parks, within urban landscapes.