A New Pattern of Biophilic Design - Awe

Advertisement

The Colorado River, at the base of the Grand Canyon.

You are walking through the low forest of pinion and juniper, enjoying the smell of the resins from the trees. It is quiet except for the magpies’ chatter. It is an intimate enclosed space, until you come to a break in the forest and walk out onto the rim of the Grand Canyon, where the space suddenly drops away in front of you. The Colorado River is nearly a mile below in the base of the canyon, the far multicolored walls of the North Rim are several miles away, and there the huge expanse of sky and clouds. You stop, your mouth drops open, your eyes are wide, and your breath is taken away. It takes you a while to wrap your mind around what you are seeing.

You are winding through the narrow streets leading to the plaza in front of the Cathedral at Reims. The towers on the front are huge compared to the surrounding buildings. You enter through one of the doors, and come into the narthex, a darkened space with a low ceiling overhead, but can see the distant view through to the transept. A few more steps and you are in the main aisle of the nave, the vaulted ceiling soars above you, the colored light streaming in through the stained glass windows contrasting with the deep shadows in some of the spaces to the sides. You stop, amazed and feeling smaller and a bit humbled.

The entrance to the Cathedral at Reims.

These are spatially induced experiences of awe. The raised eyebrows, gaping mouth, and goosebumps that characterize the expression of astonishment, (Keltner & Haidt, 2003) can arguably be applied to some experiences of awe. While associations with wonder “receptive mode of attention in the presence of something unexpected” (Frijda, 1986) are also part of the response. The best definition of awe is an experience that has perceived vastness and creates a need for accommodation in our brain. (Keltner & Haidt, 2003) It is a unique psychological and physiological response that can be induced by a space, an artwork, music, or even the presence of a powerful person. Awe can also occur when contemplating the stars in the sky or a beautiful spider web.

Advertisement

Over a decade ago, when the 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design were being developed, Awe was identified as a potential pattern, but with lack of evidence, it was suspected of being an experience that resulted from a combination of patterns, rather than possessing its own credentials; hence its exclusion from the original publication.

Today, the available research tells us a different story—that the science behind experiences of Awe is not only robust enough to identify Awe as a bona fide pattern, but that this characterization of 'Nature of the Space' has health benefits truly distinct from its counterparts.

The definition of Awe has evolved over the centuries. The roots of the term are Germanic, and it originally was associated with an overwhelming fear response; as in the fear of God. In the 1800s, Awe became associated with experiences of the sublime, a sense of combined fear and wonderment, like watching an enormous thunderstorm approaching. (Gordon et al. 2017) Today, Awe tends to be more associated with wonderment. (Allen, 2018) Intriguingly, one would think that the association with fear would indicate increased heart rate, when in fact an Awe experience caused the breath and heart rate to slow. Stopping standing still, the slack jaw and wide eyes are classic physiological expressions of awe.

The experience of Awe can make us feel smaller, humble and more charitable. (Stellar et al., 2018) These are feelings that tend to shift our focus from exclusively on ourselves and more to the bigger context of the world and people around us. We tend to exhibit more prosocial behavior after an Awe experience. (Piff et al., 2015) These are outcomes that are unique among the patterns of biophilic design, and clearly one that have great societal value.

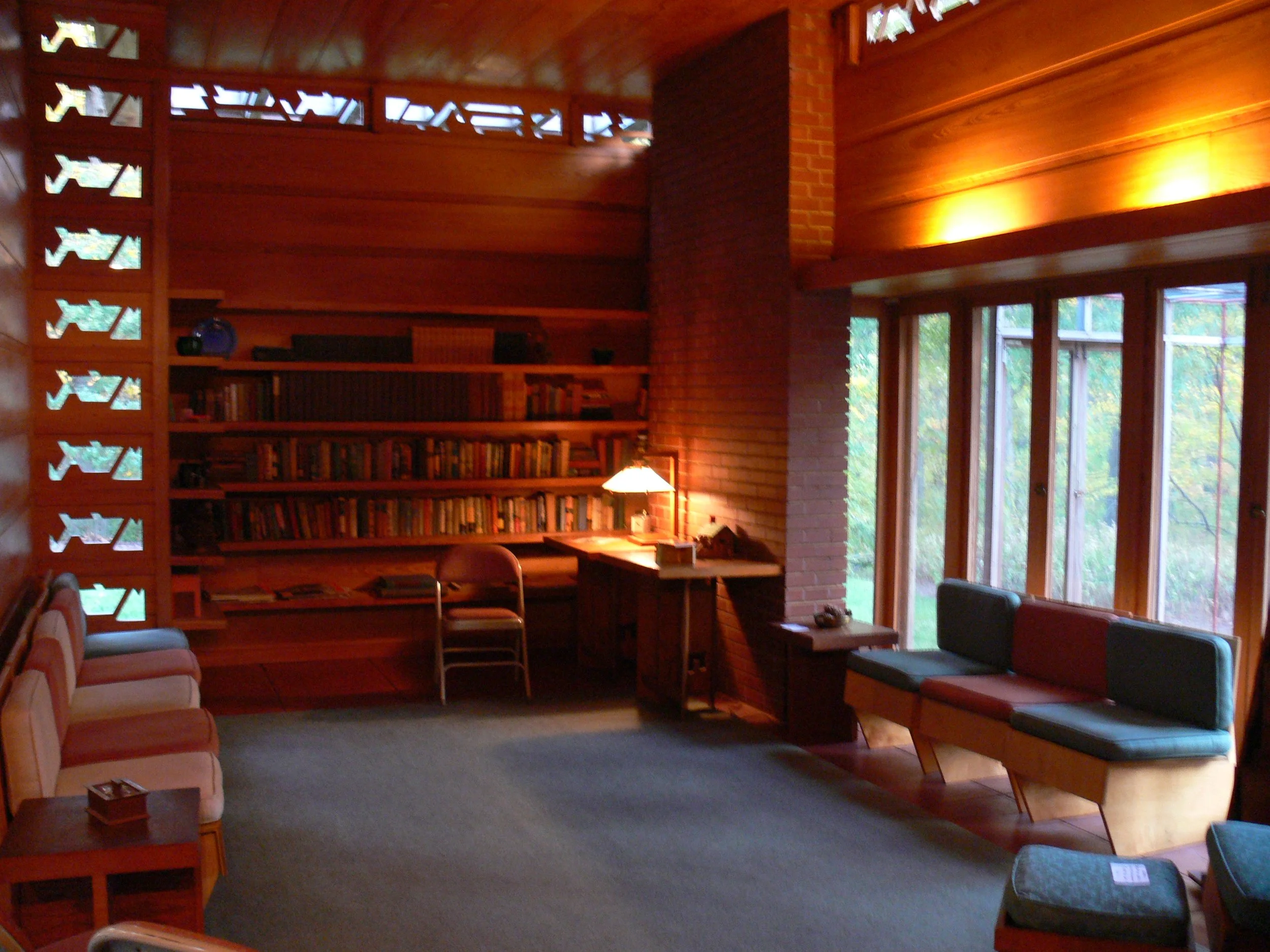

The unique entrance to Frank Loyd Wright's Pope-Leighey house can inspire a sense of awe. Photo: Bill Browning

So how do we create the experience of Awe in the built environment? Here are some examples:

Frank Lloyd Wright was a master of biophilic design. While Wright was also a prolific author, he rarely mentions anything about spatial experience, except for the sequence of ‘compression and release.’ This is an experience of awe. Wright can make it happen in a small space like the Pope-Leighey house, where you enter under a porte cochere with a low ceiling that extends into the entry hall wall. Then you go down the stairs and past the fireplace into the living room, which seems to magically expand around you. Wright increases the apparent scale of the space by floating the ceiling on a continuous band of clerestory windows, and by sliding the outer walls past a brick pier.

Advertisement

The living room of Frank Loyd Wright's Pope-Leighey house can inspire a sense of awe. Photo: Bill Browning

Wright also achieves this at a grand scale. When you approach the Johnson Wax Administration Building there is also a somewhat low porte cochere. Once inside the building you walk along a corridor with a water feature to your right. Ahead is a curving mass of brick with light spilling around the side. As you walk around the brick mass and emerge from under a balcony into the great daylighted expanse of the Great Work Room. It is an extraordinary space that has the feeling of entering a grand cathedral or an expansive oak savannah. Wright creates awe through a masterful spatial experience.

Art can produce a sense of Awe, like the work of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms. Photo: J. Mclean

Some may think that inducing the experience of Awe in the built environment can only be done with abrupt changes in the volume of space. However, there are art installations that can shift our perception of space in particularly awesome ways.

James Turrell’s Skyspaces use changing patterns of light to blur boundaries and create a sense of the infinite. Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms delight and confound our perceptions of space. Or in Paris, traveling a busy street, you round a bend and see a building wrapped in a spectacular tapestry of plants. Patrick Blanc’s green wall enveloping the Musee du quai Branley is unexpected, delightful and forces us to step back and reconsider the skin of a building. This is the power of awe.

Advertisement

William Browning and Catherine Ryan are part of Terrapin Bright Green, a green building research and consulting firm that has a special focus on biomimicry and biophilia. They have written a number publications on biophilic design, including 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design, The Economics of Biophilia and others that can be found on their website. They are co-authors of Nature Inside, A Biophilic Design Guide published in 2020 by the Royal Institute of British Architects. Bill Browning also has an introductory lecture on biophilic design, which can be found on the Living Architecture Academy.

Resources

Allen, S. (2118) The Experience of Awe, Greater Good Science Center, University of California Berkeley.

Browning, W., Ryan, C. & Clancy, J. (2014) 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design, Terrapin Bright Green, New York.

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The Emotions. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 302, quoted in Keltner, D. & Haidt, J. (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn Emot. 2003 Mar;17(2):297-314. doi: 10.1080/02699930302297. PMID: 29715721.

Gordon, A. M., Stellar, J. E., Anderson, C. L., McNeil, G. D., Loew, D., & Keltner, D. (2017). The dark side of the sublime: Distinguishing a threat-based variant of awe. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000120

Keltner, D. & Haidt, J. (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn Emot. 2003 Mar;17(2):297-314. doi: 10.1080/02699930302297. PMID: 29715721.

Perlin, J, D. & Li, L. (2020) Why Does Awe Have Prosocial Effects? New Perspectives on Awe and the Small Self. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020 Mar;15(2):291-308. doi: 10.1177/1745691619886006. Epub 2020 Jan 13. PMID: 31930954.

Piff, P.K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M. & Keltner,D. (2015) ‘Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 108, issue 6, 2015, pp. 883-899. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018.

Stellar, J. E., Gordon, Craig L. Anderson, C. L., Piff, P. K., McNeil, G. D. & Keltner, D. (2018) ‘Awe and humility’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 114, issue 2, 2018, pp. 258-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000109.